28 Cultures genrées sur Internet

Type de contribution: Mot-clés:Résumé

Le mème Internet est un phénomène bien connu et principalement associé à des interprétations humoristiques de personnes et de situations. En revanche, le féminisme fait souvent l’objet de stigmatisation dans la culture populaire, car il est fréquemment associé à des femmes dénuées de joie et d’humour et possédant une haine pour les hommes. Ainsi, les féministes et le féminisme sont parfois, sans surprise, les cibles de mèmes dérogatoires. Cependant, dans cet article, je pose la question à savoir si les mèmes peuvent être féministes et s’ils peuvent être utilisés à des fins féministes. Ma réponse est un retentissant « oui ».

“Keep Calm and Be a Feminist” (Accessed November 15, 2013)

Feministkilljoys.com[1] is the title of the newly created blog by established queer and feminist scholar Sara Ahmed. A provocative and not so tongue-in-cheek title indeed, as it invokes the often-used image of the angry, no-fun feminist who does not know how to take a joke and sees in all forms of popular entertainment the constant degradation of women. Ahmed makes the stigma attached to the label of feminism her starting point in this new project, as the blog’s tagline reads: “killing joy as a world making project.” Ahmed’s blog can be seen as a response to the continued devaluation and ridicule of all things associated with feminism in a supposedly liberated and post-feminist world.

Cultural scholar Angela McRobbie defines “post-feminism” as:

[A]n active process by which feminist gains of the 1970s and 80s come to be undermined […] it suggests that by means of the tropes of freedom and choice which are now inextricably connected with the category of “young women,” feminism is decisively aged and made to seem redundant. Feminism is cast into the shadows, where at best it can expect to have some afterlife, where it might be regarded ambivalently by those young women who must in more public venues stake a distance from it, for the sake of social and sexual recognition.[2]

These sentiments are readily observed in popular culture, as Lady Gaga once famously answered the question “are you a feminist?” with “I'm not a feminist - I, I hail men, I love men,” [3] thereby once again cementing the myth of the feminist as the joyless man hater. These sentiments are also readily echoed in digital media. Consider the tagline of the Tumblr entitled “Get Over Yourself Lady.” It reads:

This page is a response to feminist generalizations of males. Feminism has turned into accepted misandry under the guise of political correctness. Western feminists believe they are oppressed despite the fact they have the same rights and privileges as men. I’m not a misogynist. I just can’t stand feminism. It makes me itch. Misandry is prohibited. MRA is welcome. Feminists you just have to “man up” and deal with it.[4]

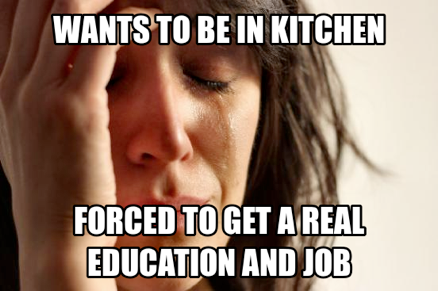

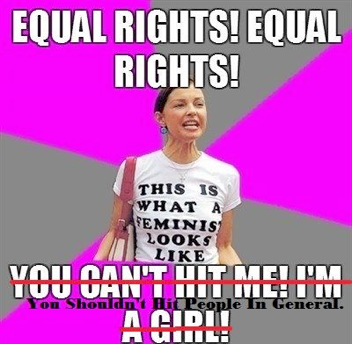

The ‘nagging feminist’ has also been made into a circulating image through the workings of Internet memes. The meme was defined in 1976, before the advent of the Internet as we know it today, by biologist Richard Dawkins. In this sense, a meme represents “the simplest cultural unit that can spread from one mind to another,” as explained by computer science scholar Michele Coscia.[5] Online, memes are more popularly known as images of certain people or situations accompanied by a witty text that often provides social commentary on a certain group. Memes often ridicule or question certain situations or people and their presumed flawed beliefs. In the case of the man hating, no-fun butch feminist, some of the ‘responses’ through memes have included the following:

Figure 1. “First World Problems” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

Fig. 2. “The Feminist Hypocrite”. (Accessed August 30, 2013)

Fig. 3. “What a Feminist Looks Like” [6] (Accessed August 30, 2013)

In the memes listed above, feminism and the ‘typical’ feminist are depicted as fickle, whiny, crazy, hypocritical, man hating, overreacting, fat, ugly and shrill. No real ‘fun’ is to be had with or by these women as they take themselves and society too seriously. Feminism itself is joyless and irrelevant, and thereby makes itself a perfect target for memes, which are predominantly “humour-centered.”[7]

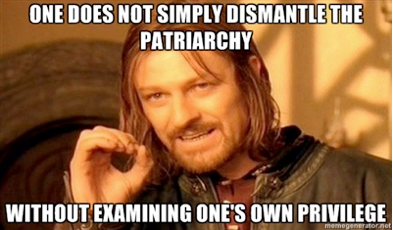

The notion of the Internet as a heterogeneous space, although somewhat utopian, allows for an articulation of counter-movements and alternative voices. In the case of Internet memes centered on feminism, it was with great joy that I discovered a plethora of subversive memes celebrating feminism, debunking ‘feminist myths’ and playfully yet critically responding to derogatory portrayals. Consider the following memes:

Fig. 4. “Dismantling the Patriarchy” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

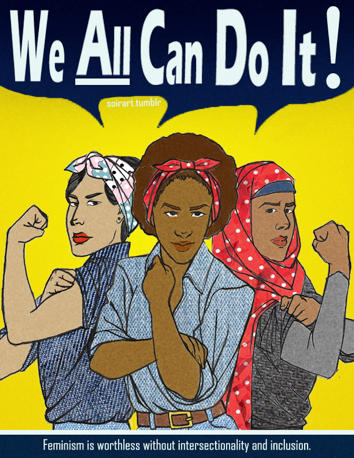

Fig. 5. “We Can All Do it” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

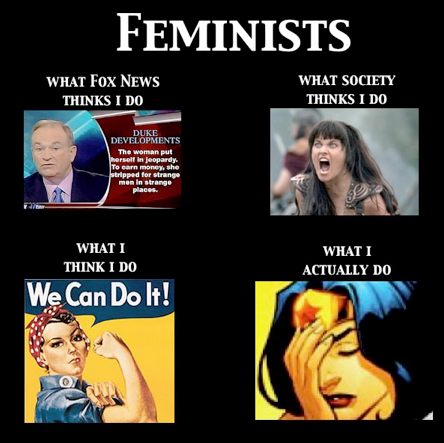

Fig. 6. “How Feminists Are Perceived” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

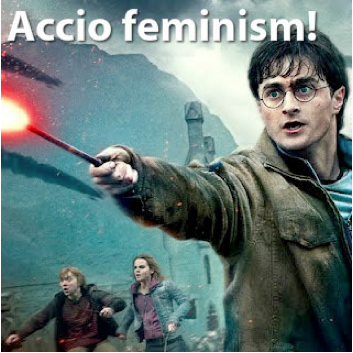

Fig. 7. “Accio Feminism” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

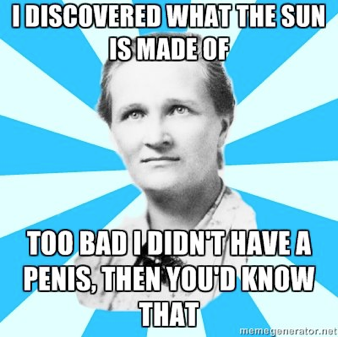

Fig. 8. “Unrecognized Scientist” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

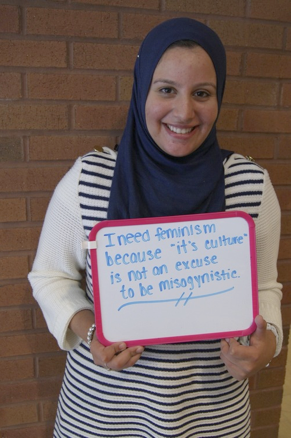

Fig. 9. “I Need Feminism Because” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

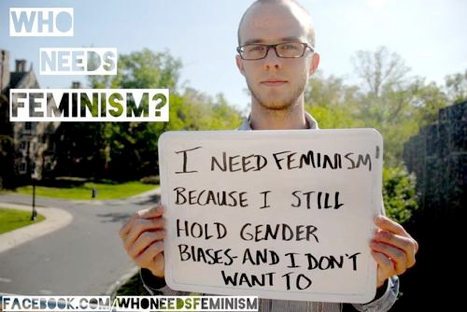

Fig 10. “Who Needs Feminism?” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

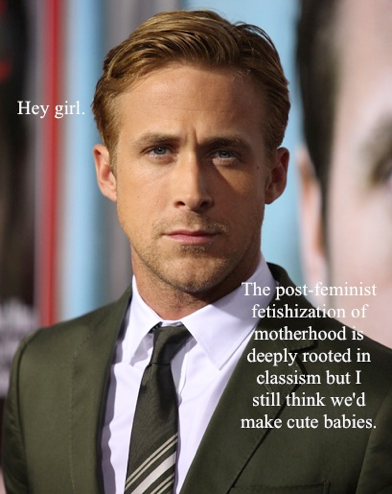

Fig. 11. “Hey Girl” (Accessed August 30, 2013)

The memes listed above each depict various instances of feminism and feminist content but in a significantly different manner than what we saw in the memes that celebrated the ridiculing of feminism and feminist ideas. The memes listed above debunk the various myths associated with feminism by playfully engaging with imagery from popular culture and the entertainment industry (the Harry Potter meme for instance), while keeping a critical eye on the workings of power and hegemony (the Lord of the Rings meme). Moreover, the distribution of these memes points to their makers’ awareness of the position of ‘the feminist’ in society (the “How Feminists Are Perceived” meme) and also serve to interrogate the processes of power that have silenced women’s voices in traditionally male-dominated spheres of knowledge (the “Scientist” meme). In addition, these memes frequently propagate the importance of intersectionality and an understanding of the workings of inclusion/exclusion (the “We Can Do It” meme) in addition to questioning and overturning the ideas of whom exactly can count as a feminist (the “I Need Feminism Because” meme). Some are more serious in nature, while others are largely playful. For instance, memes such as the “Feminist Ryan Gosling”, entertaining as they are, could convincingly be critiqued for the trivialization of feminism. However, the question of “what counts as real feminism” is not being asked here. Rather, with the showcasing of these memes, my aim has been to emphasize a different kind of participatory enterprise, one concerned with propagating feminism in its very varied and exciting facets in the very midst of the workings of current, popular and digital culture. These memes show that feminism is indeed a relevant and integral part of contemporary discourse.

New media scholar Limor Shifman defines “popular culture” through two main attributes. The first is the notion of simulacra or pastiche; an endless repetition of an image. The second is the participatory aspect of popular culture, that is, the direct involvement of users in the creation, distribution and manipulation of content.[8] In that sense, the inclusion of feminism in popular digital culture is both inevitable and necessarily heterogeneous, as users will continue to debate its meaning, importance and subversive potential through the creation of new content, among which are Internet memes. Far from the image of feminism as secluded and one-sided, these circulating memes showcase that a single definition of feminism is impossible to pinpoint, and any attempts to do so inevitably result in a distorted picture. Feminism is part of popular discourse in the digital age, and needs to be recognized as such. Moreover, these types of memes showcase that it is indeed possible to include aspects of both high and low culture, both academic and popular content, and merge them into one phenomenon (memes), thereby implicitly questioning the (perhaps artificial) divide between them in the first place.

Notes

[1] Sara Ahmed. Feminist Killjoys. (Accessed August 30, 2013)

[2] Angela McRobbie. “Post-Feminism and Popular Culture.” Feminist Media Studies, 4:3 (2004): 255–264.

[3] Lady Gaga on Double Standards and Feminism. (Accessed September 8, 2013)

[4] Get Over Yourself Lady. (Accessed August 30, 2013)

[5] Michele Coscia. Competition and Success in the Meme Pool: a Case Study on Quickmeme.com. International Conference of Weblogs and Social Media, 2013.

[6] Lucia Peters. We Are What Feminists Look Like: Amazing Tumblr Takes the Worst Fat-Shaming, Anti-Feminist Meme Ever and Turns It Into Something Wonderful. (Accessed August 30, 2013)

This particular meme is a manipulation of the original picture, depicting Kelly Martin Broderick, taken for Broderick’s feminist university group’s campaign. The photo seemed to have been manipulated beyond her control when it was posted on Facebook with the anti-feminist text and managed to gather thousands of likes and comments. In reaction, Broderick started the Tumblr “We Are What Feminists Look Like,” gathering immediate and numerous responses from individuals who seek to channel and subvert stereotyped and harmful portrayals of feminists.

[7] Paul Gil. What Is a 'Meme'? What Are Examples of Modern Internet Memes? (Accessed September 8, 2013)

[8] Limor, Shifman. “An Anatomy of a YouTube Meme.” New Media and Society 14:2 (2012): 187-203.

Milica Trakilovic is a recent (August 2013) cum laude graduate of the Research Master Programme “Gender and Ethnicity” at the University of Utrecht, the Netherlands. She also holds a cum laude BA degree in English Language and Literature, obtained from the University of Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Her research interests include questions of representation, visual culture, the social, political and symbolic role of the body, the