24 Fashion / Textile / Technology

Contribution Type: Keywords:This DPI issue sheds a new light on the relationship between fashion and technology through not only the production of materials but also the shaping of structure, the analysis of its implications and the interpretation of its end results as an interface serving as mediator between men and the urban environment in hypermodern societies.

“Socialization happens as soon as clothing is involved - the latter can also double as a cultural object.” (Descamps, 1979, p. 31) New social structures, schools of thoughts and material all influence the structure, surface and substance of modern garments. But if technological evolution leads to a future of dematerialization, virtualization and multi-sensorial realities, what will the garment of the third millennium look like? Despite its status as a frilly element in modern societies, it was a long time ago clothing became central to our existence as a social object. Flügel (Flügel, 1985, p.220) maintains that clothing would be but an episode in the story of humanity and that “men will one day (and perhaps women before them) live their lives comforted by having control over their bodies and physical environments, leaving aside the crutches of garments that once helped them take clumsy steps towards a superior culture. In the meantime, these crutches are still present. We can however ensure that our budding scientific endeavours allow us to realistically shape them and use them correctly to ease our progression.” Flügel’s (1985) garment has three defining principles that are constantly at play in the civilized world: attire, modesty and protection. Even if modesty and protection have gained in importance since clothing was adopted, it is attire that seems to be the reason why clothing came to be to begin with. It can be troubling to face the paradoxical and simultaneous existence of attire and modesty in the same sphere given that the former’s main function is to add emphasis to one’s physical appearance and attract attention while the latter is completely opposite, as it tends to make us camouflage our physical imperfection and dissuades others from looking at us. This fundamental contradiction is a source of priceless wealth in modern fashion development: fashion is a saga full of ambivalence, controversy and compromise.

Charles Baudelaire expressed that beauty was a two-faced deity: one stays in the present while the other is companion to eternity. We do not create beauty without linking these two aspects: the ephemeral and mortal together with the eternal and immortal. If fashion captivates spirits to this extent - whether positively or negatively - if it draws in people while simultaneously having a chilling effect on others, it is because it reminds us of our own dual nature, mortal but striving for immortality. Technology and fashion are, without a doubt, some of the most ephemeral domains of our time: what is new today is tomorrow’s relic. If fashion designers have always claimed to be working with an ephemeral medium that fades out as soon as it appears, some are now willing to open up a new conversation about it. Does the weaving of new technologies and materials modify a garment’s final form surface- and-structure-wise? Is giving new forms and functions to garments a valid new path of reflection in the creative process associated with future garments?

The first manifestation of fashion as a modern phenomenon - as we understand it today - took place late in the Middle Ages. The term “fashion” in reference to collective and ephemeral ways of dressing makes its first appearance in the 15th century - to dress in a new fashion becomes “to be fashionable” in the mid-16th century. The schema of fashion, from the middle of the XIXth century until today, is resumed by haute couture, confection and ready-to-wear. According to Gilles Lipovetsky (1987), fashion over the span of a hundred years, from the mid-19th century leading up to the 1960s, was defined by the creation of luxury on demand - also known as haute couture - sharply contrasting mass production. The latter was also known as confection and sought to copy exclusive haute couture creations. Original creations and industrial reproduction have since coexisted, but this marriage of convenience is defined by a clear differential in materials, technologies, brands and prices, mirroring a society that is also divided in classes with different lifestyles and aspirations.

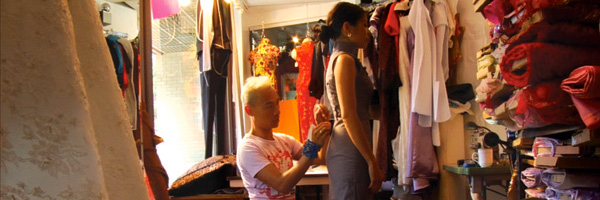

It would also be pertinent to envision the evolution of modern fashion while taking the materials being used into account - this encourages consideration of the creative process taking place in the creator’s laboratory rather than in his sewing workshop. We can see two major fields of experimentation at work: the surface and substance of new materials as well as the building of the garment’s structure.

A major shift occurred in the textile industry when Nylon was invented in the late 1930s. Artificial and synthetic textiles became more commonplace in the following decades and fashion started to progressively but rapidly appropriate an important part of new findings in many realms - chemistry, physics, even electronics.

Textile finishing allowed women a better quality of life as early as the 1960s and had a considerable impact on garments, “it became a true functional barrier with age rather than a simple protection with an aesthetic goal.” (Guillaume, 2000, p.63) Nowadays, clothing can be edible, climatic, or antibacterial.

Nowadays the term “textile” is often replaced by the word “material” - permitting for a broader, unfixed meaning. These materials allow us to roam unexplored terrains because they are completely removed from traditional references - their use quickly expanded beyond the fields they were originally meant for such as the army, aeronautics, or even medicine. Evolution in our day and age leans towards softer and lighter textiles that are easy to take care of. Signifiant textile progress first took over the military and sport realms before taking over the fashion world after being recycled and used by designers in a way completely unrelated to its original function.

New technology now occupies an ever-larger place in our daily life alongside textile. The basis of fashion and technology studies focus on these trivial but obvious observations. What constitutes a technological garment? Without official terminology and according to research done to this day, it would be cybernetic clothing blending textile and new technologies that are biological, chemical, nano-technological, numerical and electronic in nature.

Technological matter started out as the research product of chemical engineers. Early on in the 20th century, they invented a multitude of tissue protection treatments from simple finish procedures. The first study results on chemical fibres were beneficial to WWII military needs. Even to this day, most work around textile innovation concerned with smart or technological clothing does not come from the textile and fashion industries, but from telecommunication businesses, defence department laboratories and even medical laboratories. Researchers from France Telecom and Philips - among others - have presented garments fitted with keyboards and touch screens on the cuffs and microphones inserted into the collar. They are designed to facilitate the integration of computers and other electronic gadgets to the human body through the use of pockets, insertions, cut-outs, fasteners and other alterations. Style innovations are often restrictive and there are a number of unforeseen factors, especially with regards to the energy source being used.

As for media artists and fashion designers, they are thinking of a more complex and subtle integration of technological devices in garments by exploring themes of playfulness, the extension of oneself and of the second skin. The concept of the garment as a unique finished object with predefined constraints is thrown off by the introduction of new material - one that is malleable and able to communicate - that adapts to our mood or specific outdoor conditions.

The act of dressing oneself is a deeply social one; it defines not only our appearance but also our movements and subjective experiences in a given sociological context.

A true believer in a garment’s ability to communicate messages, Cheryl Sim remains surprised at the intense semantic charge sometimes carried by the traditional Chinese dress Cheongsam.

She uses hybridity as a means of exploration - both on a conceptual and formal level - to examine this garment central to her investigation. The end result - the spatial layout of a renewed documentary form - resonates in conjunction with her questioning of the garment’s influence as part of one’s identity. Here she offers a text explaining the thought patterns that fuelled her creative process.

Fashion subtly morphed over the past few years with the arrival of technological material. Modern textile and garment creation can add another dimension - that of sensory perception - to the relationship between men and their environment; the connection between the body and its environment can be established differently thanks to “smart clothing” acting as a mediating interface between body and environment. Technological clothing projects speaking of the relationship between men and their environment are especially relevant nowadays as computer technology has an ever-growing impact on our ability to absorb information and new interaction schemas. The body and its environment are simultaneously transmitters and receivers as the garment becomes their mediating interface.

Designer Hussein Chalayan is redefining the frontiers of clothing in works pairing fashion and technology with cinema and architecture. Chalayan’s garments are a mode of narration. Paranoia vis-à-vis terrorism, oppression, exile in times of war are examined in his pieces that are film- or installation-based at times and almost always high in couture. A reading of Caia Hagel’s text gives us the opportunity to get to know this creative genius whose curious nature and experimentation allows for an utopic production and an artistic process that reconciles the body with constructed environments.

As for her, artist Natacha Roussel wishes to shed light on issues encompassing technology and the body: these objects in progress that are themselves constituents of the human subject. The potential alterations of the ontological borderlands of our collective intimacy are highlighted in a politicized piece. She questions the “materiality of technology’s perceptual impacts on our relationships” as well as their function of “reliance” between the physiological behind-the-scenes of bodies and interpersonal communication.

Lastly, Emilie Mouchous gifts us a composition reminiscent of a 70‘s era sci-fi movie soundtrack. It is the soundtrack production itself that makes the composition central to our theme as it results from the use of a tissue interface linked by the artist to a synthesizer she designed on her own.