Abstract

In this reflective piece I enact a curious collision between “Inevitable Transition,” the theme of this issue of Studio XX's .dpi , my own artistic practice, and my thinking about Hurricane Sandy. To say that something is inevitable is to state that it is unavoidable, that something is bound to happen. There is a certainty involved in the inevitable. The word transition suggests a process or change from one state to another. I have taken the opportunity presented by this themed call to revisit some of my artistic work, to explore how thinking through the concept of “Inevitable Transition,” might deepen my understanding of my practice. I bring to my considerations, the very real Frankenstorm, Hurricane Sandy, the largest storm of its kind to hit North America. It is imperative to make the connections among colonization, environmental devastation, climate change, corporate greed, and power. Can slow art, poetic, abstract, and conceptual art; meaningfully address the urgent need for widespread understanding of these strengthening relationships? How do I, in my art practice, wrestle with the brutalities of colonization, and the associated environmental catastrophes brought on by unbridled and unregulated capitalism and corporatism? As an artist, I feel the need to break the silences surrounding these processes.

Abandoned. Photo: Roewan Crowe

In my conceptually informed artistic practice I irreverently craft together video, text, animation, theory, photography, performance, and activism. I have often stated in the past that I am in the “Western phase,” of my artistic practice in which I explore the imaginary, geographical and cultural landscape that we call “The West.” I now understand that this is not a phase, rather it is foundational to my art practice. I am interested in the tactical deployment of self-reflexivity and transformational artistic practices. For me, living and working on Turtle Island, in the declared nation state of Canada, necessitates artistic production and creation that acknowledges the context of colonization in North America. I situate myself within the frame of the traumatic Western narrative as a queer feminist settler who is invested in wrestling with this history. I recognize that the legacy of the West and colonization is still replicating itself. I enter into this fatal wounded environment—a violent and xenophobic narrative—to explore the possibilities that open up when I inhabit both the story and the form of the Western. I work to subvert, play and reckon with these tales of trauma. This is my artistic resistance.

Queer Grit , a stop-motion animation, is the first creative work I did in which I seriously positioned myself as a queer feminist settler with an awareness of colonization. In this work I wanted to ground myself in a specific place/landscape to ask questions about belonging and histories of patriarchal and colonial violence. Being queer for me has meant banishment and exile from my family and the rural communities that I imagine I once belonged to. I bring to my work this deep understanding and queer knowledge of being refused the ability to return to a place I called home. Jane West and her handsome trans-lover enact a return to the scene of trauma, to the Hollywood Western and to spaces where white supremacy and heteronormativity are regulated through the use of violence. The very idea of belonging is troubling given histories of dispossession and colonization.

Video : Queer Grit by Roewan Crowe

In the Western imaginary, the landscape has been emptied out of its Indigenous first residents, replaced by cowboys and farmers, settlers and Indians. New stories of patriarchal familial succession take the stage. Captivity narratives fill the land with burning wagons, screaming white women and the cavalry rushing in. Manifest destiny is writ large – sometimes on T-shirts sold by The Gap.

The classic Hollywood Western is seen as an enduring myth, some even say history (Walker 2001). The collision of North American colonial history and Hollywood Western narratives created the space that I work within. The “classic Western” (Wright 1975) produced this powerful colonial myth that has layered itself upon the land, our bodies, and our collective imaginary. Violence is at the core of these narratives.

Gas station. Photo: Roewan Crowe

digShift is a multi-channel video installation where I engage in a personal, historical and environmental reclamation. This work marks my move from behind the camera into the frame as a performer. In my previous work, Jane West, a plastic action figure from Marx's Best of the West toys, acts as my doppelganger. By stepping into the frame and performing as Jane, now a self-reflective cowboy, I am able to explore and dig into the shadow of the site. Now Jane the action figure is not my only doppelganger, the abandoned gas station, the land it sits on, and history of the land all shift to become my ghostly doubles.

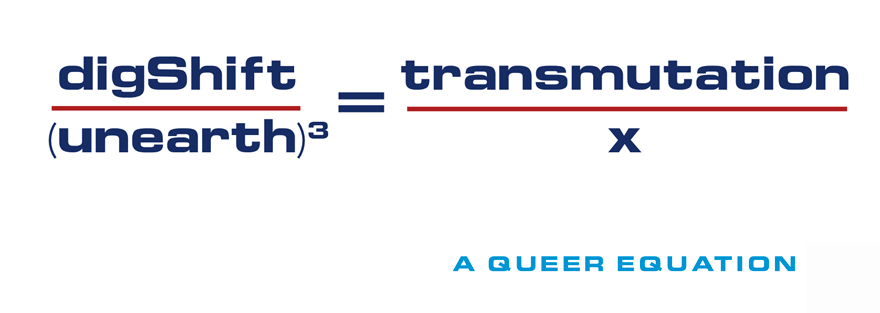

Equation. Photo: Roewan Crowe

digShift consists of four large projections: three video poems, “Landscape,” “Window,” and “Dig;” and a fourth video projection entitled “digShift.” The projection “digShift” contains three split-screen video works, entitled “digShift,” “Shadow,” and “Inside.” Central to each video are: repetitive, performative gestures such as digging and walking; site-specific images and sounds of the abandoned gas station and its surroundings, from both inside and outside of the building; poetic inquiry into the core concepts of the site which include the ideas of landscape, window, digging, inside/outside and shadow; and carefully crafted sounds from the site that have been layered with music, composed by Garth Hardy, and with an unidentified voice performing a short poem.

In each video poem a word, constructed from the image of the site itself, appears and disappears. The installation plays with notions of time, and reveals itself as slow art. You have to wait for the story to unfold, just as you might wait for something to happen if you lived in a nearly abandoned prairie town. The video poems appear in a timed sequence. They are carefully orchestrated to move people from one poem to another, to move the viewer emotionally and physically, to draw the viewer across the space. As the videos come on in sequence and repeat, they build slowly until the words, music and images layer each other. This “slow art” piece takes 20 minutes to view in its entirety. Second dig , an artist chapbook published by As We Try and Sleep Press, accompanies the exhibit.

Dig video still. Photo: Roewan Crowe

The work of digShift is drawn from a site-specific artistic exploration and performance. I dig into the shifting layers of meaning at an abandoned gas station in Elstow, Saskatchewan, just 20 minutes southwest of Saskatoon on the Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16). I work with video, poetry, and a queer equation to fathom the uncanny process that unfolded here. Literally and metaphorically, I dig deep into the personal, historical and environmental layers of the land, to perform a reclamation in collaboration with this wounded terrain. I explore this abandoned landscape to reclaim a personal history, to explore the history of colonization, to map the industrial expansion and the rural decline following it—from railroads to factory farms to oil fields—and to imagine and perform an artistic, land-based environmental reclamation.

Window video still. Photo: Roewan Crowe

Canadian highways are profoundly marked by abandoned industrial landscapes. I was particularly drawn to this station just outside of Saskatoon. For over 15 years, I have reluctantly yet faithfully returned to this site from my past to take photographs, perform, write, theorize, dig and shoot video in an attempt to imagine some sort of meaningful reclamation for this compelling and toxic landscape. Through various media, I engaged with the site to try to understand why this land/memory site has so strongly attached itself to me. As a child, my family lived briefly out back of the gas station in a trailer. It was a typical Saskatchewan story of the poor and working class in the 1960s. My father worked in the potash mine, and my mother worked at the restaurant in the gas station. While this place holds a personal connection for me, it took on a more vivid significance over the years. The gas station came to symbolize the excesses of the West—both the prairie West and the “first world” West—and the processes of colonization, industrialization and environmental destruction.

Video : Shadow Video Poem by Roewan Crowe

I see myself as digging into my own shadow, the shadow left on the land by the cowboy, by colonization and by processes of industrialization. I see my acts of creation as generative in that, it is through these processes that I think and feel more clearly. I become the queer feminist settler, through the repetitive act of digging. In the labour of repeating the act of digging, I also transform my relationship to the trauma of the West (colonization) and the persistent shadows of settlement. Through the creative process I more profoundly understand the shadows that are left on the land.

During my artistic engagement at this site over the years, I tried unsuccessfully to refuse and sever my connection to this place. But as I made art about the site I came to understand and accept my responsibility as steward to this particular place. Over time, with sustained artistic engagement and “digging,” my final artistic task became clear: I imagined removing the rusting tanks that lay beneath the earth, leaking contaminants into the soil and ground water. After preliminary research and planning, I returned to the gas station in May to gather more information about who owned the site so I could begin to write grants in order to get the gas tanks removed. When I returned to the site in August of the same year with a plan to present to the small village, I learned that in the three months since my last trip, the tanks had actually been removed and the land sold.

The removal of the tanks from this wounded site left me feeling temporarily released from my habituated return to this site. I was left with many questions. How do I understand the process of this project, namely the potential of the imagination to effect real-life transformations? Arjun Appadurai writes, “The imagination is now central to all forms of agency, is itself a social fact, and is the key component of the new global order” (1996). How do artists make material that which we imagine? Here I turn to Gayatri Spivak, who claims that “an appeal to the imagination is a material practice” (Spivak 2004: 616).

Today, post Hurricane Sandy I sit with these questions and some of the art I have created, slow art no less, in the face of the rapid acceleration of climate change. Hurricane Sandy, like many of her predecessors, was not just a ‘storm.' There are no natural disasters. The drastic changes in weather are man-made. We are experiencing climate change in real time. Just as there is widespread silence about colonization in North America there also exists a remarkable silence about climate change.

As an artist, I feel that I am engaged in the continual process of becoming. What does it mean to have a profound understanding of myself as a queer feminist settler, and what does my work bring to the larger project of decolonization? Colonization was presented as an inevitable transition, and still is the inevitable transition of resources from Indigenous people to the settlers/colonizers, to capitalism, and then corporatism. These processes are ongoing, an attempt at totalization, the relentless absorption of everything into capitalist accumulation . There has been no room for any slackening of the exploitation of the earth, for any decline in profits.

Given these seemingly inevitable transitions, what are the inevitable transitions for the queer feminist settler artist? It is imperative to make the connections among colonization, environmental devastation, climate change, corporate greed, and power. Can slow art, poetic, abstract, and conceptual art; meaningfully address the urgent need for widespread understanding of these strengthening relationships? How do I, in my art practice, wrestle with the brutalities of colonization, and the associated catastrophes brought on by unbridled and unregulated capitalism and corporatism? As an artist, I feel the need to break the silences surrounding these processes. I am not certain where this heightened sense of urgency will take my artistic practice. I believe, though, in adding to editor Deanna Radford's theme for this issue, that it is both a necessary and inevitable transition.

References:

Appadurai, A. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

Sharpe J., & Spivak, 2002. “A Conversation with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: Politics and the Imagination.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 28 (2): 609-624.

Walker, J. (2001) ‘Captive images in the traumatic western: the searchers, pursued, once upon a time in the west, and lone star', in Walker, J. (ed) (2001) Westerns: Films Through History, New York: Routledge.

Wright, W. (1975) Six Guns and Society: A Structural Study of the Western, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Image credits: Roewan Crowe

Sections of this piece appeared in No More Potlucks, Issue 07: Wound, 2010.

The artist thanks Manitoba Art Council, Winnipeg Arts Council, MAWA, Video Pool Media Arts Centre, Plug In ICA, Jarvis Brownlie, Ken Gregory (mixing sound), Garth Hardy (original composition), and Zab (Equation Design).

Transdisciplinary artist Roewan Crowe is energized by acts of disruption, transformation and the tactical deployment of self-reflexivity. In her queer, conceptually informed artistic practice she irreverently crafts together video, text, animation, theory, photography, performance, and activism. She enters into fatal wounded landscapes—often violent and xenophobic —to explore the possibilities that open up when artists walk through the shadows of the world. She subverts and plays with these shadows. This is her artistic resistance. In 2007 she launched her solo show digShift . In May of 2008, in collaboration with Mentoring Artists for Women's Art, she curated the Art Building Community Project , which launched 10 new works and a weekend symposium. She just completed her experimental text entitled, Quivering Landscape . She is an Associate Professor in the Women's and Gender Studies Department at the University of Winnipeg and Co-Director of The Institute for Women's & Gender Studies.