24 Fashion / Textile / Technology

Contribution Type: Keywords:Abstract

If it weren’t for the body, Hussein Chalayan might be another kind of artist. He is a very serious lover of visual art, design, anthropology and philosophy, and has a sincere interest in evolution and history. He makes films and strange objects – the unforgettable egg capsule that Lady Gaga arrived in at last year’s Grammy’s, and was ‘birthed’ from to perform Born This Way to a startled and adoring audience, for example – all of which contain his deep fascination for, and investigation of, the world we live in – and the ideas that propel us in our world towards its next expression. But it’s the human body that Chalayan loves most, and wishes to use as his primal canvas. Not just as a ‘place’ on which to describe fleeting sensations and current colourways – but as an anthropological site where deeper things about the human condition can be expressed.

Photo: Groninger Museum

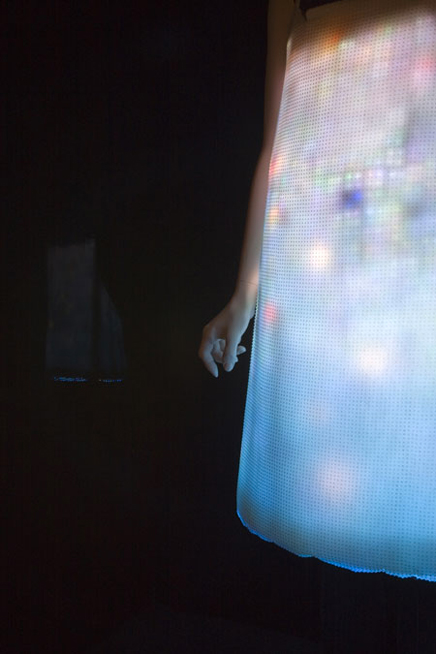

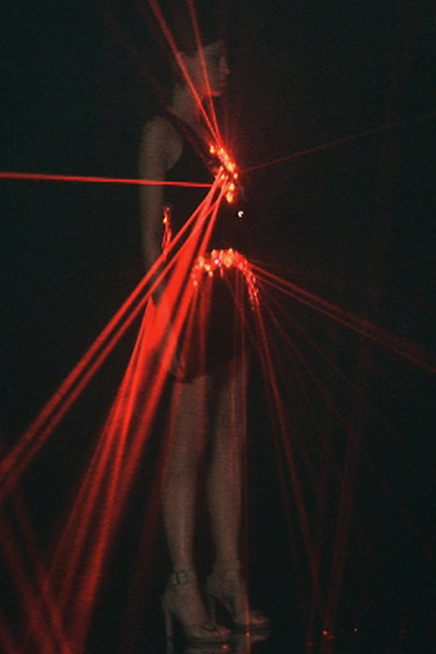

As a contrapposto to this earthy anchor, Chalayan exalts technology. “Technology is really the only vehicle through which you can do new things. Everything else has already been done before, one way or another,” he says. His many collaborations with experts in technological fields – most recently from crystal laser inventors (for the SS08 dresses that emit light), to live web projectors (for his SS12 show in Paris where models’ mouths were projected onto a large screen with instant feedback via cameras inside their champagne flutes, “It was primal”, he said. “You could see their lips and teeth and right into their mouths”), allow us to experience viscerally the mind-body connection by transporting us, inside our bodies vested in exceptional clothing, to the places our minds soar to.

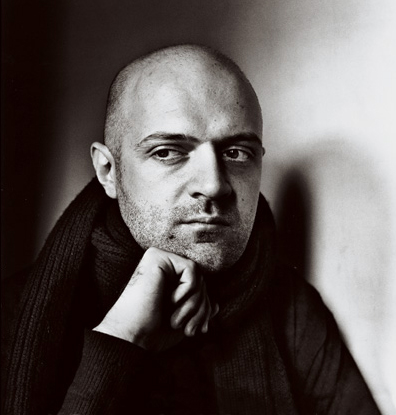

I interviewed Chalayan at the opening of his first retrospective exhibition at Groninger Museum, Holland, in 2005 – the same year that he represented Turkey at the Venice Biennale with Absent Presence, a short otherworldly film starring Tilda Swinton. Unlike any of the other fashion divas that I have worked with, he was soft-spoken, humble, calm and introspective, and he wanted to talk about philosophy. Perhaps because of the rare vision and maverick energy that inform each of his projects – he flourishes within the rarified, air-kissing fashion world without compromising an inch of his integrity. This warm, open man is a proper genius who continues year after year to surpass himself.

One of fashion's quietest achievers, designer Hussein Chalayan creates clothing with a sculptural aesthetic that draws from architecture, engineering and politics.

Scissors poised in hand, Hussein Chalayan is hovering over a mannequin with just five minutes left to the opening of his ten-year retrospective at Groninger Museum in Groningen, Holland. Skin-tone tulle is flying everywhere. His intense yet soft, dark eyes dart along his berserk trail of scissor cuts and, finally, Chalayan is happy with the refinements.

Standing beside him, curator Sue-An van der Zijpp shrugs. “He wanted to take all the clothes off [the mannequins] this morning and iron them,” she says, “I had to stop him. But here we are pruning the Garden Dress – a fat creation of bulbous tulle inspired by humankind's need to control natural forces – at the last hour. They're ideological pieces and I do understand, but he fiddles to the end.” Chalayan grins, tidies up the mess and explains: “When you have a passion, you have to do it.”

He walks downstairs past more mannequins, these with disturbing cone-shaped heads and futuristic shoes, pausing at the pod-like vessel he created for a new international art project sponsored by the BAR Honda Formula One racing team. The pod has a utopian design language reminiscent of a spread in Archigram magazine. Next to it, an animated film depicts the pod in flight, a womb-like form carrying a female passenger from London to Istanbul.

Photo: Groninger Museum

Every piece in Chalayan's exhibition shows subjects familiar but not quite human and, on closer inspection, busily exploring their identities. There is wallpaper that matches prints on dresses; glass boxes that encase models who are cleaning windows; and props and furniture. The creator looks at them affectionately. “I try to progress, to do something not yet done and to discover new ideas and create a new language along the way,” he says, the passion he speaks about visible in his eyes and in the muscular way that his compact body lingers around his dresses.

Chalayan is a rare breed of fashion designer who doesn't pander to glamour alone. He believes in the deeper power of his craft and employs a language that weaves fashion with technology, film and architecture.

“His blurring of the boundaries between the traditional functions of clothing brings to mind those furniture designers who thought of furniture as a flexible membrane that mediates between the body and the built environment,” comments Caroline Evans at fashion and art college Central Saint Martin's, London. Evans is reader in fashion history and theory at the college, which Chalayan graduated from in 1993.

Even then Chalayan's curiosity and experimentalism set him apart from his peers. At his graduation show, The Tangent Flows , Chalayan paraded dresses sprinkled with iron filings that had been buried for weeks in a friend's garden. Their earthy half-decomposed allure was so unusual that high-end London retailer Browns bought the entire collection and hung it proudly in its windows.

Since that lauded debut, the star student has transformed into a professional designer with his own label and produced all kinds of exotic works, twice crowning him British Designer of the Year (in 1998 and 2000). There was ‘airmail' clothing made of an untearable paper called Tyvek that could be folded and mailed, and remote-control dresses with moveable flaps mimicking airplanes. There was a wearable head-rest, dresses of sugar glass that were shattered onstage with hammers, a kite designed for Rapunzel to make a safe descent from her tower, and customised balloons that helped propel models bouncing on a trampoline towards the Divine.

One of his most awe-inspiring shows was Afterwards (autumn/winter 2000), in which models wearing only under-slips removed the covers from chairs and donned them as dresses before folding the chairs themselves into suitcases that they walked off with. The finale saw a model stepping into the centre of a round coffee table and attaching its removable top to her belt, forming a bustle-like skirt of flat wooden discs. By the time she cleared the stage, Chalayan's living room-like set had vanished. “The show was inspired by the war in Kosovo,” van der Zijpp recalls. “It was ‘oh, this is just a chair – no, it's my favourite dress', a fashion moment so unforgettable that it was truly moving.”

Photo: Groninger Museum

One audience member who had never seen his work said the show made her cry. “It was so unexpected. When the coffee table became a skirt there were squeals and then a standing ovation; there was so much emotion. It was the only fashion show I'd been to that touched me so deeply, and I wasn't alone. I looked around the room at the end, when the Bulgarian Gypsy group had stopped singing, and there wasn't a sound in the whole place. I saw tears running down people's faces.”

Chalayan acknowledges the serious themes in his work. “I grew up in [Turkish] Cyprus when the wall between Muslim Turks and Christian Greeks was erected,” he says, referring to the UN buffer zone enforced since 1974. “From one day to the next, people that shared the same DNA were cut off from each other. I've been obsessed ever since with understanding division and separateness and what makes us different and similar, and how this relates to the human body.”

Later, Van der Zijpp expands on this theme. “His work has a feeling of homelessness about it, not just because he's been transplanted from Cyprus to London but because it's pretty much the post-modern condition. Even if a lot of people don't see into what he exposes about the underbelly of things, the clothes he designs, and the furniture and film props he uses to elucidate their meaning, make them more than a second skin. They become philosophical question marks and social commentary and a kind of moveable architecture.”

Photo: Groninger Museum

An example of this is the aeronautical engineering technology used in the remote control dresses. “This suggests that perhaps it is not only the dress but the self that can be engineered, fine-tuned, technologically adjusted and played with,” Evans says.

Characterised by its graphic shapes, austere cuts and crisp fabrics, Chalayan's clothing even draws comparisons with architecture. The designer collaborated with architect Zaha Hadid to design the scenography for a Charleroi Danses ballet production of Metropolis in 2004. “We saw how fashion and architecture can communicate in response to the body,” says Patrik Schumacher, a spokesman for Hadid. “The way that Chalayan interlinks them is genius.”

Schumacher feels that Chalayan and Hadid use a similar creative process. “One technique we use is called ‘making strange', whereby we rotate and invert and distort traditional building proportions to create something more visionary. Chalayan seems to be ‘making strange' with clothing, by restructuring proportions of garments to create something completely new and non-traditional.”

The same year, Chalayan collaborated with London firm Block Architecture to design the first Hussein Chalayan store, in Tokyo. “It wasn't a case of handing over a brief,” recalls Milly Patrzalek, assistant to Chalayan. “It was a collaboration that Hussein steered and was involved with each step of the way.” Chalayan describes the interior as “a meeting between architecture and fashion, as well as a meeting of worlds. Olive trees and washing lines on the lower floor and a faux open-air cinema upstairs create an interplay between urbanism and ruralism, making you feel outside when you are actually inside.”

Despite his sky-high achievements, the notoriously shy Chalayan won't say much about himself. “I'm typical. I read and watch TV and enjoy travelling and spending time with friends,” he says, simply. Patrzalek disagrees with the description.

“Hussein's like a library,” she says. “He's ferociously studious, like a worldly monk full of ideas. But he's not all brain; he has a very sensitive side. He notices the foibles in people and is a good judge of character, which means that he has hired a team that is very familial and loyal; most of us have been around since the beginning.” She grins and adds, “He's not into celebrities and doesn't like fashion events, though. We beg him to ‘please just get us in the door' so that we can go to the parties.”

The office does foster autonomy, if not air-kissing. “He once asked an in-house dress designer to do the technical drawings for the coffin, boat and wooden exterior of the trampoline in the Temporary Interference show [with the balloons; in1995],” Patrzalek remembers. “She taught herself how to do it from books and when the drawings were presented to the carpenter, he was amazed at the quality. No one ever says ‘I've never done that before, I can't do that'. It's a democratic, creative, busy place to be employed.”

Photo: Groninger Museum

In June 2005, an ever-busy Chalayan screened his short film The Absent Presence at the Venice Biennale and had it ranked among the ‘top ten hottest British exhibitions' by The Telegraph. He unveiled his 2006 women's spring/summer collection, whose theme was the debate of Turkey's inclusion in the European Union, and which sold record amounts of garments to buyers. Shortly afterwards, at the men's fashion shows in Milan, Chalayan's Touch Wood show explored superstition across cultures in eerie clothing emblazoned with chessboard prints and evil eyes.

Chalayan's last-minute amendments in place, the exhibition in Groningen was an out-and-out success. At the launch, museum director Kees van Twist said with feeling: “This pioneering designer unites cultures and opens dialogues between them, without ever hinting that one is superior to the other. We can learn from him.” Chalayan, sitting the quiet maverick beside him, smiled affably at the audience, their loud cheers of applause ample proof that fashion can make a stitch or two of difference.

Hussein Chalayan. Photo: Groninger Museum

Caia’s personality profiles, travelogues and design and art critiques appear regularly in magazines and TV networks internationally. Her dream sequence on snakes as part of video artist Roy Villevoye’s short film Beginnings, won the Tiger Award at the Rotterdam International Film Festival. She has won Best Feature Article at the New York Folio Media Awards for her profile on design-demi-god Rem Koolhaas, and Best International and Best Experimental Short Film at the Brooklyn Film Festival for script and performance in Under the Swell. Her wicked essays with photographs by Tim Georgeson in the monograph Blood; Or a Long Weekend With My Wife's Family, were exhibited at Stills Gallery in Sydney, Australia, to critical acclaim. Her chapbook Acts of Kindness and Excellence in Timestables was published with fanfair at The Cupboard, and her short story, Desire, headlined the vol 44, no.4 issue of The Denver Quarterly and was selected as a notable essay by Robert Atwan in The Best American Essays 2011.