Résumé

Jessica MacCormack échange son point de vue sur les médias sociaux, l'art à l'ère du numérique et notre rapport à Internet, tout en abordant ses collages numériques ainsi que sa pratique socialement engagée en compagnie de sa collègue artiste montréalaise, Claire Ellen Paquet.

I met Jessica MacCormack in the summer of 2012. We became Facebook friends and, as “Jess Mac”, she has been a staple in my newsfeed ever since. Despite the fact that we both currently live in Montréal, Facebook chat seemed like the best way for me to finally ask her some of the questions I had about her practice, and what follows is the (edited) result.

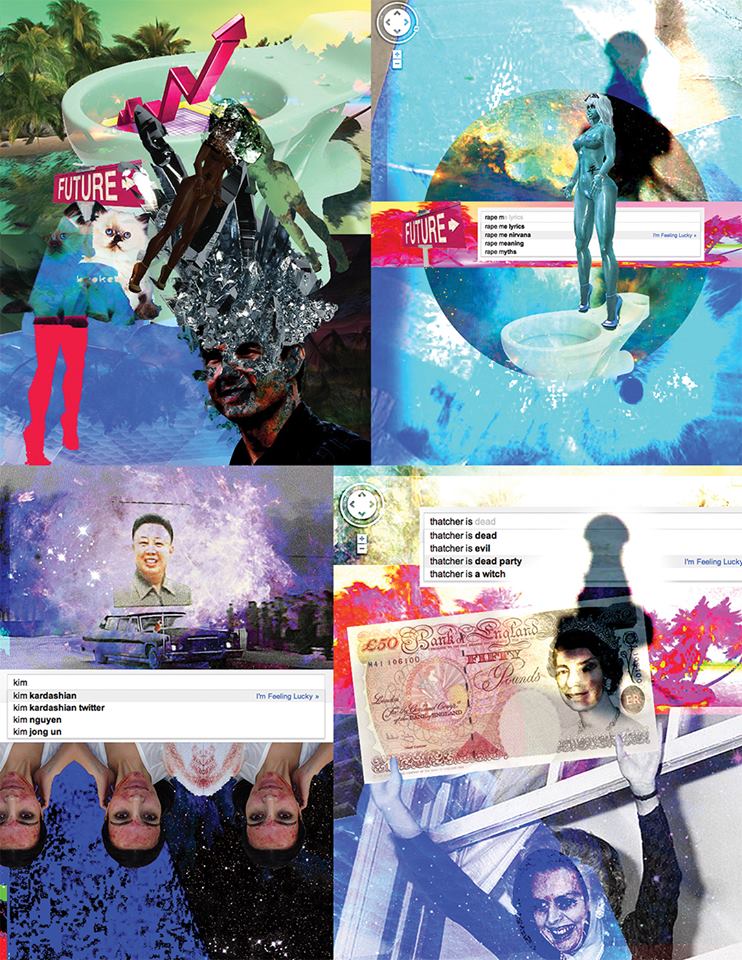

Jessica MacCormack, 2013. Permission of the artist.

Claire Paquet: You share your digital collages on Facebook, so I feel like I’m exposed to your practice on an everyday basis. In your artist statement you refer to your interest in “cultural platforms and distribution networks” and I wondered if you could talk about social media in that capacity, and what role it plays in your socially-engaged practice.

Jess Mac: Well, I think that I would first and foremost consider facebook one of the ways I stay in touch with people I have worked with on projects in various communities, for instance the folks I worked with in Winnipeg on art projects through Crossing Communities.

Recently, though, there was this moment when I realised Facebook wasn’t like MySpace or Friendster, in that it had some kind of staying power. It was taking over our lives and identities in real ways. I wanted to find a more creative way to interact with it, so I could free myself from some of the obvious pitfalls.

CP: I feel like I’m at a crossroads in my relationship with Facebook. I’m constantly trying to decided where to draw lines between the personal and the “professional” online. I think that could be in part because more and more of my life is spent online, and I’m increasingly thinking of it as part of my “real life”.

JM: I feel like “Jess Mac” is a thing that people relate to in a specific way, that differs quite radically from my interpersonal relationships in the day to day. I feel like most of my professional life is generated online, though – people actually “see” what I do here, and less so in other areas of my practice and life.

This was especially noticeable when I was working as a professor; the two identities [of professor and artist] seemed at odds at times.

CP: As someone invested in social issues and with a social practice dealing with definite “real life events”, do you feel like there’s a disconnect [between what you post online and the events to which you are referring]? Or does it help to emphasize your understanding/investment in these issues?

JM: Hmm, yes, I find there is a real disconnect in experience and emotion. In engaged community practices there is a real sense of impact and feeling, but on Facebook everything is leveled into this flat landscape of points and images. People feel unseen and frequently inadequate compared to others’ popularity or seeming happiness.

In community work we realise more how we are all suffering, and peoples’ actual strength of character and struggles. Facebook feels like a game of tag.

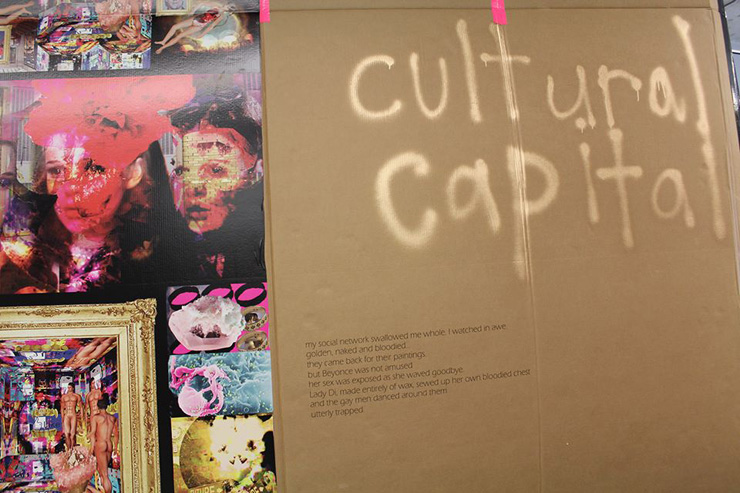

Jessica MacCormack, detail of The Bastard Lovechild of Thomas Hirschhorn and Tracey Emin, 2012. Photo: Jessica MacCormack. Permission of the artist.

CP: I think that’s why I’m so interested in the digital collages – they really interrupt the general aesthetic and flow of what’s going on in my newsfeed.

JM: They are really influenced by Tumblr and my presence there, but I’m also trying to critique these methods of communicating and identifying.

I was making [these collages] out of necessity/survival/pure exhaustion from teaching full time. I actually started making them when a close friend committed suicide. It was an easy, quick, and accessible way to have an art practice of sorts that I could fit into the cracks of my day to day – a space I could feel and be weird in, be a person for myself and not an object for others.

CP: I’m really drawn to how prolific you are and I’d wondered if it was out of necessity or the conscious decision to saturate the web with your imagery. The compulsion makes a lot of sense to me.

JM: Art always comes from real life constrictions/laws/accessibility, meeting up with history and resources. Art is made by people who also must struggle to [make it], but to even be able to struggle must already have access to so much.

[Through this work] I was able to escape into being more honest about who I am. I guess I’ve had to play a lot of roles in my life, so I’m used to this paradox/dissociation. Sometimes I prefer personas to personalities, the distance. But I also find online personas give me courage to take risks in my life.

CP: The Internet is very dissociative in a lot of ways. Especially before I discovered ‘fat politics’, I craved a space where I was not my body. I definitely turned to the Internet as an outlet at a young age to deal with that feeling, and I’ve maintained that attachment.

JM: I didn’t have the Internet until I was 27. In my childhood I had a “radio show” and recorded my ramblings for hours on end. Then as a teen I wrote a lot of angsty poetry and smoked, but I really was a mess and needed help. I felt very alone and alienated most of my life – I wonder what it would have been like had there been the Internet.

I guess that’s also what the collages are about – still trying to show something that is impossible to say.

CP: Facebook is so text-based that I feel like your insertion of images is a kind of intervention – do you see it that way at all?

JM: Well, yes, I guess I also noticed how suddenly everyone started posting images with text on Facebook. It seems like the kind of content that is normalised shifts every 6 months. It started feeling like people were moving further and further away from the personal and relational and more into a Tumblr - esque reblogging style. I wanted to punctuate (or puncture?) that shift.

CP: Does that ever make you anxious, do you feel like you need to keep up with how quickly it shifts?

JM: I feel like I can’t be critical of what is happening because it changes so fast and we are all so submerged. When the like button came out everyone thought it was so horrifically stupid, and now it impacts our self-esteem!

I have 0 popularity. There are many digital artists online with 100 likes on every image. I guess I’m not doing what people like.

CP: Do you find that discouraging? I feel like it could be a little freeing as well.

JM: Yes, both. I don’t really believe art is meant to please people. But at the same time… I sometimes get paranoid that people are actively ignoring me as a way of putting me down. Most people on Facebook actually have very little idea of who I am or what I have lived through. So I guess I guess I fear judgments that are [not empathic] to me as a whole person.

CP: Do you think that context is important to understanding your work?

JM: Yes, but I am also constantly shifting contexts. So maybe that is equally important. Many people think I am just an animator.

CP: They’re only acquainted with one particular persona, perhaps. I guess our personas are half what we put out there and half what people choose to pay attention to.

JM: Which just reminded me of the Lana Del Rey avatar…

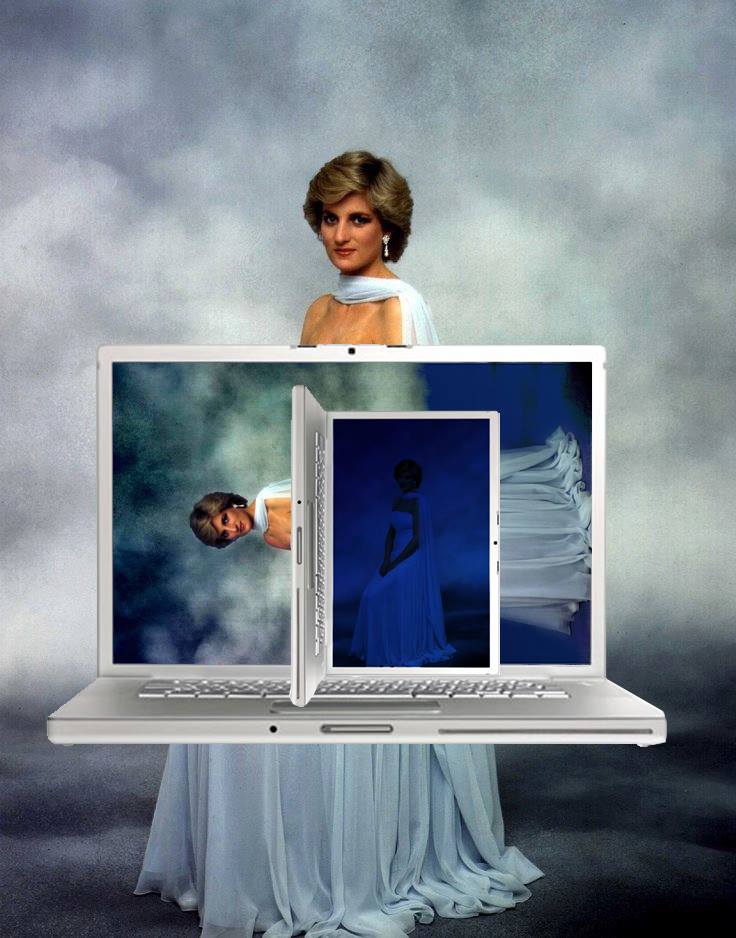

Jessica MacCormack, 2012. Permission of the artist.

CP: Why are you interested in Lana?

JM: Because she is an avatar IRL!

CP: A lot of the women you refer to I’m also really interested in – like Princess Diana, I’m fascinated by her and the accounts of her self-harm.

JM: That is definitely what interested me, the paradox of her public persona – the self-harming princess. It was validating and yet very odd. How could a woman with so much power be so small inside? When I was a teen/young adult I was confused by this. There is a lot of blood in my collages!

CP: I’m interested in how self-harm exists as a kind of fad that’s enabled by the Internet, though I’m not really sure how or if I want to address it.

JM: I think an open dialogue about self-harm can be really helpful.

CP: Because it seems so inherently private.

JM: Yes, but it is also about needing to express feelings that are difficult to express. So the publicness is about that too. Maybe my collages are Facebook cutting? Expressing raw feelings that I can’t find words for, but not on the body.

CP: The Internet becomes the body.

JM: Yes! I’m actually quite scared of what the Internet has done to me; I feel I cannot quantify it in any way. It is an addiction unto itself.

Jessica MacCormack, 2013. Permission of the artist.

Claire Ellen Paquet is an artist and writer currently based in Montréal. She completed her BFA at Mount Allison University in Sackville, New Brunswick, where she was closely involved with Struts Gallery & Faucet Media Arts Centre. Her practice is focused on systems of coping, contemporary mediation of relationships, and the mysterious. She is a co-founder of the Cyber Scouts - an organization devoted to the fostering of successful internet personas.