28 Gender(ed) Cultures on the Internet

Contribution Type: Keywords:Abstract

When surveillance restricts civil liberties, those who do not conform to what is deemed “normal” are targeted first. In such a climate of fear, the easiest reaction to increased limits on our internet freedom might be an attempt to “play by the rules”, or to limit our speech altogether in order to protect ourselves. However, we argue in this essay that the exchange of civil liberties for the safety of being “left alone” only works on the surface. Sooner or later, the surveillance state catches up and demands further compliance. The alternative strategy – resisting the dismantling of our civil rights – does not come so easily.

Image: Flickr.com, user laverrue. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic.

There is a fairly widespread perception that open, powerful, advocacy for queer rights is a relatively recent phenomenon. Depending on the country, that might even be true. But Germany's gay rights movement had a much earlier start. In 1897, the world's first gay rights organization, the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee), was founded in Berlin. For the 36 years of their existence, they advocated for the repeal of anti-gay laws, gathered signatures of prominent intellectuals (including Albert Einstein, Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Leo Tolstoy) in support of those repeals, aided in the legal defense of prosecuted homosexual people, conducted and published academic research, and founded one of the first sexology research institutes, the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft.[1]

But this is not the story of the many great things they did. This is the story of the one very awful thing they did, without ever meaning to do it.

Some of the WhK's work included surveying and interviewing people about their sexuality. They collected large quantities of data on the actual sex lives and identities of gay and lesbian people, and used the evidence they found to bolster their advocacy efforts. Their data included names, birth dates, and sometimes even addresses of people they interviewed.

But one day in the spring of 1933, their work was abruptly ended. The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was attacked by a National Socialist student group. Their library was sacked, emptied out into the streets. Joseph Goebbels, in one of his first public appearances after being appointed Propaganda Minister, gave a speech to a mob 40,000 strong in the square outside. They burned the books, burned the research, burned everything except for the data about homosexuals – their names, addresses, birth dates. That data was retained.

Students marching in front of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft prior to pillaging it. May 6, 1933.

*** 2 ***

Edward Snowden's leaked documents about the National Security Agency's Internet surveillance activities have justifiably gotten a lot of attention. But there is a particular aspect of this abuse that hasn't been talked about nearly so much. It's the retention of data. The NSA already can store communication from many sources for up to 6 years – that's all communication, not just the communications they "target". They are aggressively building capacity for massively increased storage, and Moore's Law dictates that eventually – and perhaps sooner than we think – they'll be able to capture and store the vast majority of all of the world's electronic communication and keep it indefinitely.

*** 3 ***

We like to believe that in this “modern” world we won't suddenly descend into widespread persecution and witch hunts. But it's never easy to see the waterfall coming until you're going over it. In Russia today, that's starting to become more and more clear. The new law against 'homosexual propaganda' effectively makes being gay in public illegal. Police indifference towards assaults on gays completes the picture. And past speech, speech that would have been legal before the law was passed, has already been targeted. Artist Konstantin Altunin, who painted a picture of Vladimir Putin and Dmitry Medvedev wearing lingerie, was forced to flee the country due to police persecution, without ever being explicitly told what alleged crime he was being investigated for.

The first person to be convicted under the new law may be a man named Dmitry Isakov, and his case perfectly illustrates how social pressure and fear can effect censorship. He stood in the town center of Kazan holding a sign saying "Being gay and loving gays is normal. Beating gays and killing gays is a crime!” He was arrested and beat up by plainclothes police officers, then later released. When he continued his protest the next day, his own parents stopped him, his father tackling him while his mother ripped his sign from his hands. Their intent may have been to protect him from persecution, but their method of choice was forcibly silencing him. His charges were dismissed until a teenager in another Russian province saw a picture of Isakov's protest online, and made a formal complaint. The simple fact that a record of Isakov's speech existed online in some form and could be seen by a Russian somewhere was enough to get him arrested.

*** 4 ***

A lot of our speech is recorded, nowadays. The line between what's public and what's private is increasingly blurred, as well. Is what we post on our Facebook walls public? What if we have maximum privacy settings, and only allow our friends to see? What if we posted something that was originally only visible to our friends, and then Facebook's privacy policies changed? Is our speech retroactively public?

Section 319 of the Criminal Code of Canada already makes a distinction between what's permitted in private speech vs. what's permitted in public speech:[2]

Every one who, by communicating statements, other than in private conversation, wilfully promotes hatred against any identifiable group is guilty of

(a) an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

(b) an offence punishable on summary conviction.

*** 5 ***

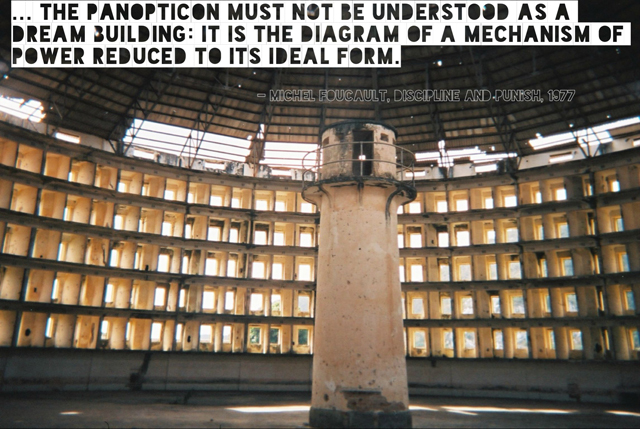

Jeremy Bentham's idea of the Panopticon has been referenced many times in academic literature, and notably by Michel Foucault's elaboration of the workings of disciplinary power. Foucault first tackled this theme in the 1975 book Discipline and Punish: the birth of the prison. There, he argues that it is more productive to understand the emergence of prisons – the panopticon is the ultimate example of such – not as a desire for more humanitarian forms of punishment, but rather, as an interconnected effort to discipline bodies and discourage dissidence. Foucault explains that subjects emerge from the works of disciplinary power, which meticulously render the embodied individual more docile and useful, and thus less likely to resist disciplining:

The individual is no doubt the fictitious atom of an 'ideological' representation of society; but he is also a reality fabricated by the specific technology of power that I have called 'discipline'.[3]

But what are we building when we allow the retention of our data? It amounts to a panopticon that extends backwards and forwards in time. A whole new dimension, literally, is added to the concept. Not only must we always worry about whether what we say is being spied upon, we can never be free of that worry. Our worry is not confined to self-censoring our speech or bodily actions in the present, so that it is acceptable to the current powers that be; slowly we start to realize that self-disciplining must go so far as to avoid the attention of the worst version of whatever future powers we can imagine, because this discipline could be retroactively applied. The data is, after all, there, available to the grasp of any sufficiently powerful entity. It could be exposed to everyone in the whole world if any entity that had access to it was sufficiently careless. Something formerly understood as paranoia begins to look more and more like a well-considered, rational position. Foucault’s assertion that power is not only restrictive, but also productive, becomes apparent by its capability of creating complying individuals that spontaneously decide against resistance.

Once we know we are always being watched, not only by whoever might be watching us today but also by any number and type of indefinite, potential future spooks and snoops, we feel the need to begin to edit ourselves, and edit our selves.

http://i.imgur.com/SqJj9Ws.jpg Text overlay added by Jon Oster.

In her 1990 book Gender Trouble, Judith Butler develops the idea that what we say and do is not simply reflective of what we are, but actually constitutes what we continuously become, through a performative process. This is a familiar idea. Think of the way in which we change how we present ourselves all the time: on a first date or at a job interview we are different people than when we are alone with an old friend. According to Butler, this process of becoming is a constant, something that we perform at all times, consciously or not. That we live in society helps shape this performative process by constraining which sorts of becoming are acceptable and which aren’t.

*** 6 ***

That data that the Nazis kept after their sack of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft's library was used, of course. It formed the basis of the so-called “Pink Lists”, and contributed to the thousands of gay men sent to concentration camps.

The Internet is a powerful way for people to challenge gender ideals, try on identities, or connect with support groups. It is a fertile environment for countercultures that challenge assumptions of what is purportedly normal. But that can only remain true if the privacy of Internet communication stays strong. That is the only way to ensure multiple possible becomings.

Notes

[1] Lauritsen, John, and David Thorstad, The Early Homosexual Rights Movement: (1864-1935). Times Change Press, 1995.

[2] http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/fra/lois/C-46/page-156.html

[3] Foucault, Michel. Discipline & Punish. Random House of Canada, 1977.

Natália Perez is a multidisciplinary artist working in theatre, music, and computer-based art. She is currently working on her PhD at the Freie Universität Berlin. She is interested in questions of gender, social justice, ethics, culture and history, and how they all relate to theatrical practice. Born in São Paulo, she has also lived and worked in Montreal, Brussels, Seville, and Canterbury.

Jon Oster specializes in computer security and encryption. An avid reader, he also plays the piano, ukulele and bass, and likes to create weird music and soundscapes in Max-MSP. Originally from Saskatchewan, he has been traveling around Europe for the last couple of years and for now he is settled in Berlin.